AABANY gathered 20 other associations for the 3rd Annual Pre-Holiday Multi-Association Gathering, on Tuesday, November 11, 2025, at 6:00 p.m., at the New York City Bar Association. The evening featured a potluck dinner, and a CLE Program on Wellness Resources, which included a Fireside Chat focused on veterans in the legal profession since this year’s event fell on Veterans Day.

As the evening began, guests gathered around a vibrant potluck table featuring an array of dishes representing the diverse cultures of the co-sponsoring bar associations.

The spread included scallion pancakes, lo mein, samosas, roasted pork, dumplings, pigs-in-a-blanket, fried rice, Caribbean-spiced chicken, and homemade baked goods, among other offerings.

Holidays can be emotionally and mentally challenging for many, especially those navigating identity transitions, loss, or professional pressures. This year’s CLE focused on veteran experiences, resilience, mental health, and navigating civilian legal careers after military service. Because this topic has often been neglected, it was especially meaningful to conduct this dialogue on Veterans Day.

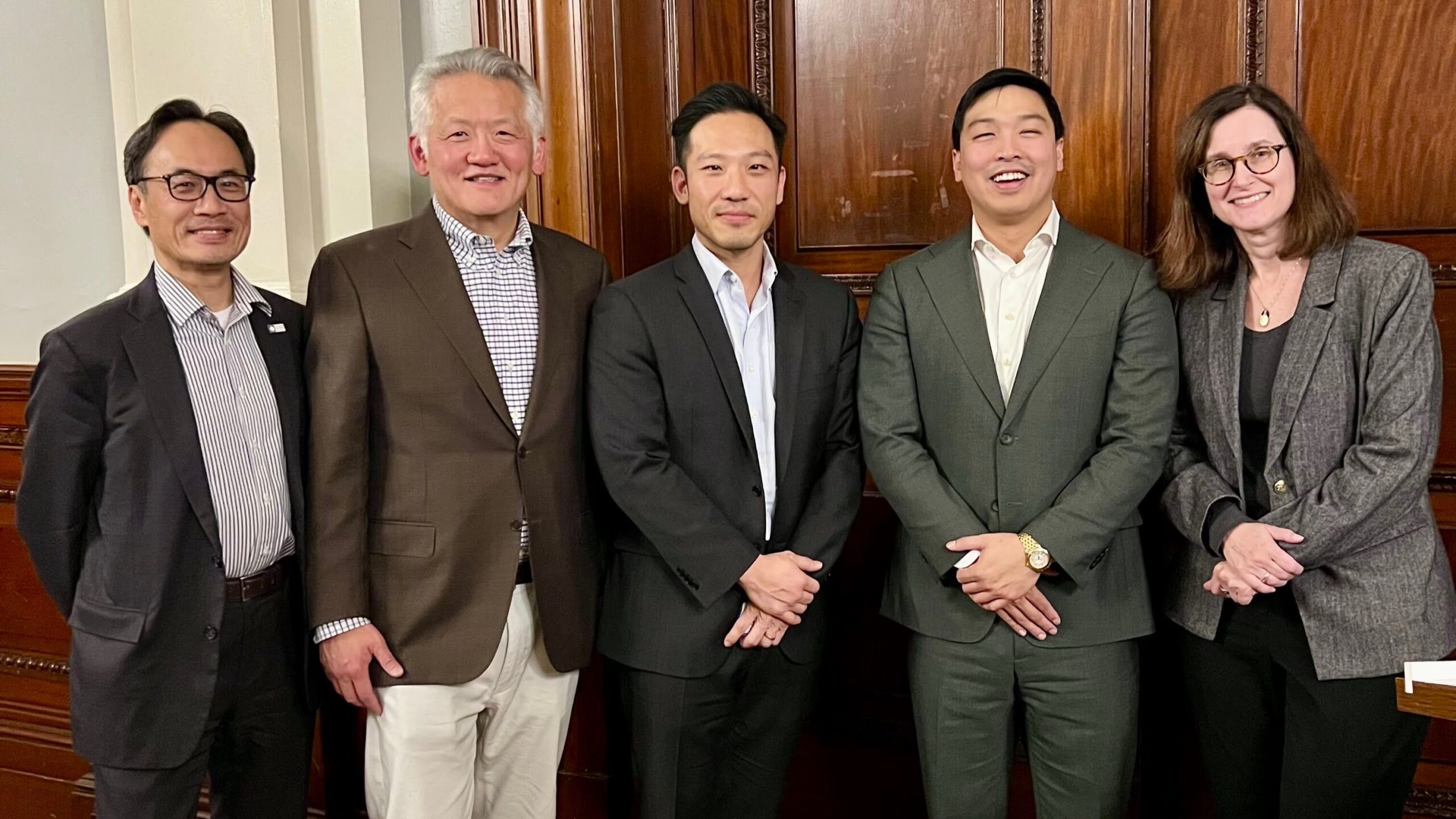

The Fireside Chat featured a conversation between Amos Kim, Co-Chair of AABANY’s Military & Veteran Affairs Committee, litigation associate at Baker Hostetler, and Austin Cheng, U.S. Army veteran, attorney, and CEO of Gramercy Surgery Center. It was moderated by Benjamin Hsing, President of AABANY and Senior Counsel at Bayes PLLC. Meredith S. Heller, Attorney from the Law Office of Meredith S. Heller PLLC, also spoke to share wellness resources from the New York City Bar Association.

Austin described the often invisible challenges of transitioning from military life to a legal career. Reflecting on his return from service, he shared: “In the military, I knew exactly what I was responsible for. Every day had structure. There was clarity, purpose, and a team. When I returned to civilian life, I suddenly had too many choices — too much freedom. And that can be overwhelming.” Without that structure, veterans are suddenly faced with what many of us take for granted — choice. But for those used to clear orders, set routines, and defined missions, choice can feel less like freedom and more like instability.

Austin also shared that when he returned from service, the emotional weight of reintegration was immense. He reflected, “I just remember getting back on a Sunday. I was happy to get back home to my family after four years. I can see my mother, she was very different from when I saw her last.” Returning home is often imagined as a moment of relief, closure, or celebration. Yet for many veterans, the process can also be challenging and even painful. They need to rebuild identity, redefine purpose, and adjust to a life no longer shaped by military structure, urgency, or routine. Austin shared that he was suddenly faced with family responsibilities, including taking over his mother’s business, while grappling with these changes. It was during this time that he decided to pursue a J.D.

The difference in adjustment, Austin noted, is not merely about finding a new job and life, but about perspectives. While civilians may show respect and appreciation for service, understanding the mindset of military service requires more. And this goes both ways – veterans also may need to understand the perspective of the civilians, understanding that they are limited in their perspectives. As Austin stated: “I don’t think civilians ever played the role of a military person. I think what was more important at that time when I was transitioning out was me being able to understand the mindset of a civilian.” This highlights a key shift: successful reintegration does not mean expecting others to fully understand the military experience, it means understanding others’ perspectives.

Furthermore, cultural change can be difficult to get used to. Rather than operating within a single shared purpose, veterans entering the legal profession must now find purpose, build teams, and cultivate trust in a system where perspectives differ, and where collaboration is shaped not by command, but by conversation. Amos stated, “In the military we’re made to have like-minds, whereas here, in the team-building process, we have similar minds.” In the military, unity comes from sameness: same mission, same standards, same purpose. In the legal profession, unity must be built through difference: through debate, collaboration, and shared understanding.

However, they also benefited much from their time in service. Reflecting on how military training shaped his sense of purpose and discipline, Austin said: “I think being in the military gave me a certain level of resilience and perspective…. It’s war, so you have to kind of do certain things under very stressful conditions.” That sense of resilience, formed through years of training, responsibility, and operating under high-stress conditions, would anchor him in both law and leadership.

Amos added similar reflections, noting that even after transitioning into the legal field, many habits shaped by military life remain deeply ingrained. Attention to detail, strategic thinking, and discipline continue to guide his work. He shared that he still wakes up at 4:00 a.m. every day because his body and mind remain conditioned to that rhythm. The expectations in the military: precision, accountability, and intention, become part of who you are.

Amos also described the intensity of expectation, precision, and discipline expected in the military: “Operating in the military is more along the lines of what you’re doing to the right every time. There’s no room for error, and there’s no room for any other ideas on how to do it better. It’s the best way to do it, and that’s all.”

Austin’s and Amos’s experiences as service members not only shaped how they approached their mission, but how they later perceived work, purpose, and responsibility in civilian life and the legal profession.

After dinner and the Fireside Chat, attorneys, law students, judges, and professionals connected and exchanged stories during the networking time. The conversations were not just about their work, but about their families, cultural backgrounds, and personal journeys. Several attendees shared that it was refreshing to step away from case files and deadlines to connect as people, not just as professionals. The connections built between attendees of different backgrounds were personal, heartfelt, and deeply meaningful.

We thank all co-sponsoring associations for their continued support and generosity in sharing the diverse food for this event:

- Asian American Judges Association of New York

- Association of Black Women Attorneys

- Brehon Law Society

- Caribbean Attorneys Network

- Dominican Bar Association

- Filipino American Lawyers Association of New York

- Haitian American Lawyers Association of New York

- Hispanic National Bar Association – Region II (New York)

- Hellenic Lawyers Association

- Korean American Lawyers Association of Greater New York

- Metropolitan Black Bar Association

- Network of Bar Leaders

- New York County Lawyers Association

- New York State Bar Association

- New York Women’s Bar Association

- NYS Asian Jade Society

- NYS Academy of Trial Lawyers

- South Asian and Indo-Caribbean Bar Association of Queens

- South Asian Bar Association of New York

- Ukrainian American Bar Association

Events like these demonstrate AABANY’s ongoing commitment to wellness, community, inclusion, and shared storytelling within the legal profession. On this Veterans Day, we were proud to honor not only those who served, but also those who continue to serve through law, leadership, and empathy.

In addition to the associations and the speakers, we would like to thank Jonathan Nguyen, Gloria Tsui-Yip (AABANY Membership Committee Co-Chair) and Kwang Woo Andy Kim (law student from Rutgers Law School – Newark) for volunteering at this event.

Photos from the event can be found at this album here.

“Purpose doesn’t end when service does. It simply takes a new form.” -Jade Simmons, transformational speaker, author and former concert pianist, from her book Purpose the Remix