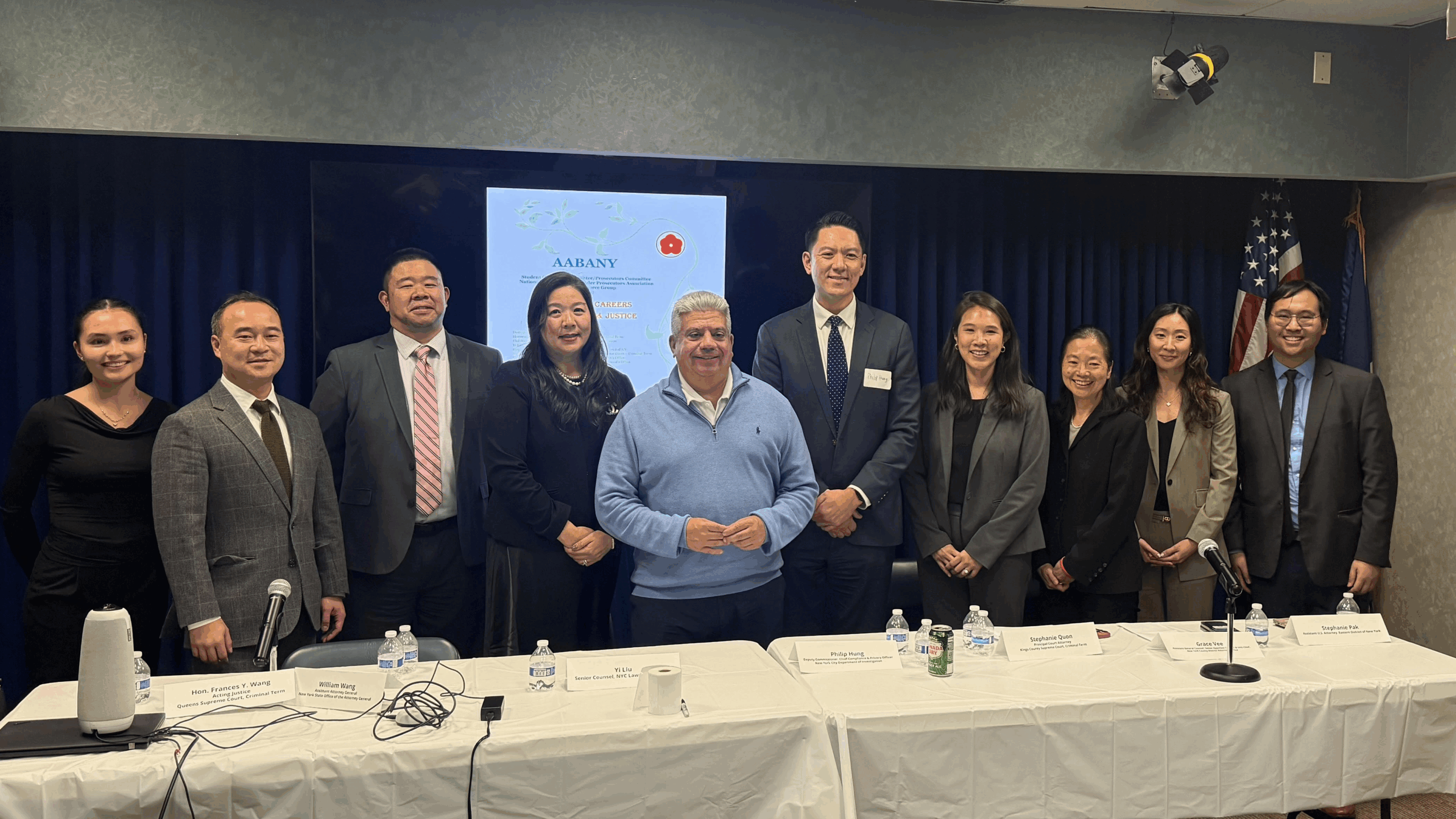

On November 25, 2025, AABANY’s Prosecutors and Student Outreach Committees joined the National Asian Pacific Islander Prosecutors Association (NAPIPA) to host an event called “Pathways to Careers in Government & Justice” at the Kings County District Attorney’s Office. The hybrid program, available in person and via Zoom, brought together law students, early-career professionals, and seasoned public servants for a wide-ranging discussion about what it means to build a career — and answer a calling — within the criminal justice system.

The event opened with a warm welcome and participants enjoyed a delicious spread of food, featuring dumplings, fried rice, chicken wings, and noodles. The event then quickly moved into a dynamic panel conversation featuring prosecutors, judges, court attorneys, and representatives from major government agencies. Each speaker traced their path into public service, revealing how mentorship, curiosity, and unexpected opportunities shaped their careers. The following judges were also in the audience: Hon. Phyllis Chu, Hon. Danny Chun, Hon. Marilyn Go (Ret.), and Hon. Don Leo.

Panelist Hon. Frances Wang (Queens Supreme Court, Criminal Term) described a childhood spent moving across Taiwan, Singapore, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and finally the United States. Adjusting to new cultures, learning English, and navigating unfamiliar schools, she found herself in a third-grade classroom where a teacher told her, “You ask a lot of questions. I think you’d make a good lawyer.” She had never heard the word lawyer before, but the encouragement stayed with her. Years later, that early spark grew into internships, mock trial competitions, prosecutorial work, and eventually a judgeship.

Her story echoed a theme that ran throughout the night: the profound and often quiet influence of mentors (teachers, supervisors, judges) who saw potential long before the speaker did. Many panelists noted that their career trajectories were not linear. They relied on mentors to clarify possibilities they did not know existed, whether in appellate litigation, regulatory enforcement, oversight and investigation, or judicial work.

William Wang (Assistant Attorney General, New York Attorney General’s Office) and Stephanie Pak (Assistant United States Attorney, U.S. Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of New York) and Yi Liu (Senior Counsel, New York City Law Department) offered clear, accessible explanations of their bureaus and divisions, from affirmative litigation to labor and employment matters, and gave students a rare inside look at where public-sector lawyers can make a difference. Phil Hung (Deputy Commissioner, Department of Investigation) described DOI as “the city’s watchdog,” explaining how the agency investigates fraud, waste, abuse, and corruption across virtually every city entity. For many students, it was the first time seeing how interconnected the city’s justice and accountability systems truly are.

Stephanie Quon (Principle Court Attorney, Brooklyn Supreme Court – Criminal Term) described roles that receive less public visibility but are essential to making the courts and prosecutors’ offices function. She explained the intellectual rigor and responsibility that come with drafting decisions, researching complex legal issues, and supporting judges in high-stakes cases ranging from violent felonies to gang conspiracy, fraud, and bias-motivated crimes.

Grace Vee (Assistant District Attorney, Manhattan District Attorney’s Office) shared her journey to becoming an Assistant District Attorney, which started from a brief externship at the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office while she was still in college. What began as a two-week externship quickly became a defining experience. She spoke about how impressed she was by the dedication of the prosecutors, the sense of mission in the office, and the profound public service component of the work.

That early exposure stayed with her. She went on to law school, determined to return to the Manhattan DA’s Office, and she did. Grace became an Assistant District Attorney and remained in the role for 30 years (just recently celebrating her 30th anniversary at the Manhattan DA’s Office), building a long, distinguished career grounded in community protection, ethical prosecution, and public trust. Her story demonstrated that the spark of public service can begin early, but its longevity is sustained by commitment, discipline, and a deep belief in the work. During Grace’s description of her journey, she thanked Judge Marilyn Go, also in attendance in the audience, as her mentor and role model. This moment was especially moving, showing how mentorship has passed on and created a lasting legacy of service within the legal community.

Grace’s narrative resonated particularly strongly with students, showing how a single moment — an externship, a mentor’s encouragement, a first exposure to courtroom advocacy — can set the foundation for a meaningful career.

Across all these narratives, one message stood out: there is no single path into public service, but every path requires integrity, courage, and a willingness to step forward.

As the conversation deepened, several speakers reflected on the unique role of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) attorneys in public-sector positions. They underscored that representation matters not only for visibility, but for trust. Many communities remain fearful or skeptical of government institutions; seeing people with shared histories and cultural understanding in these roles can make the legal system feel more accessible. Public-sector lawyers often become bridges between communities and the courts, between fear and understanding, between wrongdoing and accountability.

The panelists’ honesty about the pressures of the work, whether in sentencing decisions, overseeing investigations, or handling trauma-heavy prosecutions, imbued the discussion with realism and deep humanity. Their candor also reaffirmed that commitment to public service, despite its difficulty, remains a powerful way to shape the world with purpose.

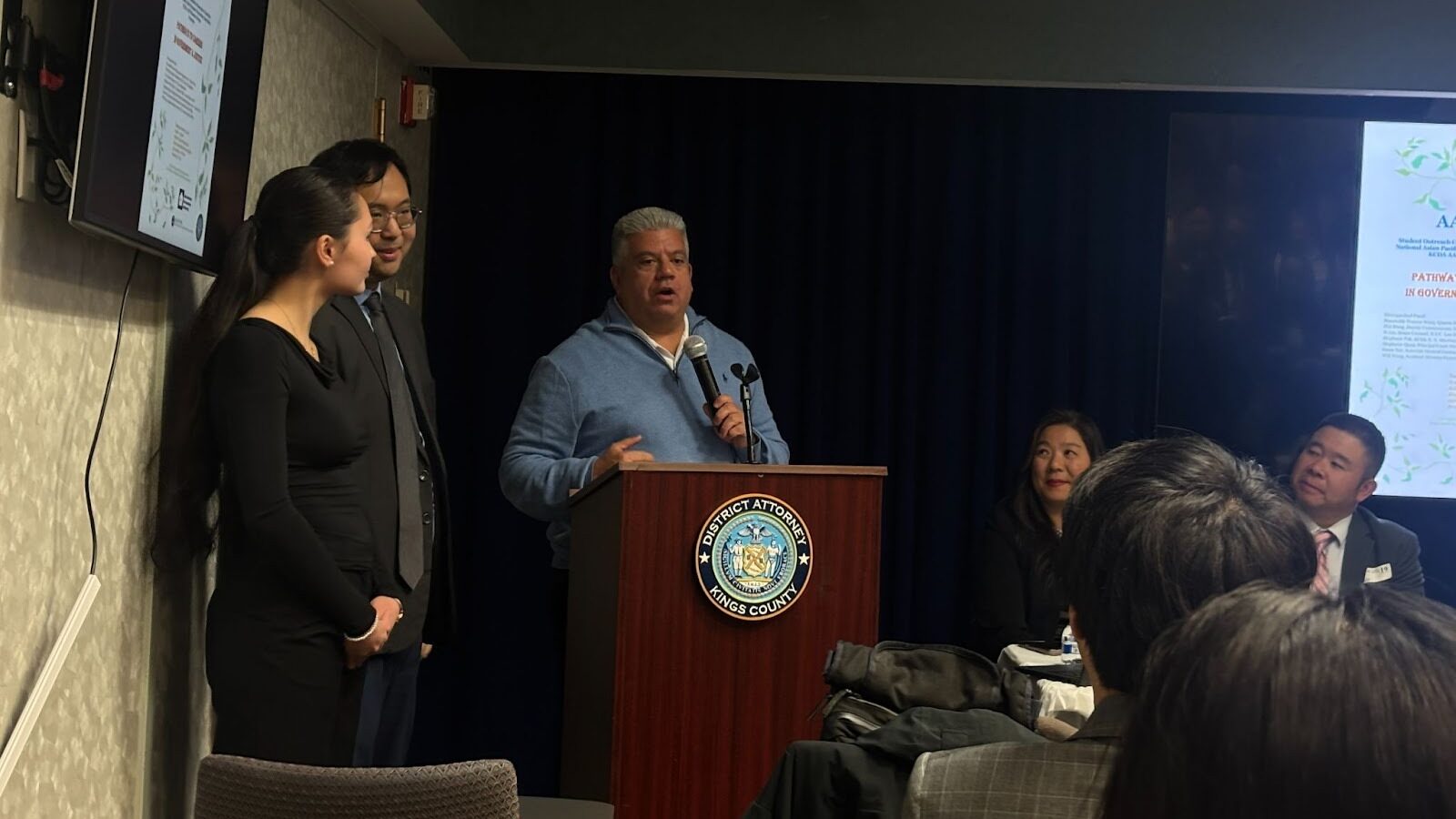

A Visit from Brooklyn DA Eric Gonzalez: A Call to Serve

Midway through the evening, Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez stopped by to offer words that many attendees described as especially moving. He spoke frankly about the critical need for representation in public service, drawing on his own background as a Latino community member and prosecutor.

He emphasized that the justice system needs attorneys who reflect the diverse communities of New York, especially in moments of heightened distrust. “People are really afraid of government,” he said, noting that this fear is prevalent across Asian, Latino, Caribbean, and Black communities. DA Gonzalez emphasized that increased representation and participation of more minority community members would help address this issue.

DA Gonzalez stressed that losing talented young lawyers to the private sector would have consequences far beyond the walls of a single office. The public, he reminded everyone, depends on committed public servants who can build trust and foster accountability. His message was both caution and encouragement: stay, serve, and know that your presence matters.

Thank You to the Prosecutors Committee, Student Outreach Committee, Panelists, and the Kings County District Attorney’s Office.

What distinguished this event was the sincerity running through every story, every piece of advice, and every reflection. The speakers did not simply outline career paths; they opened windows into the human experience of being a public servant. They spoke about challenges and doubts, but also about the moments that reaffirmed why they chose this work.

Hearing about the speakers’ individual stories made students and attendees realize that they could do it too, and witnessing their dedication, passion, and commitment to their jobs firsthand was definitely impactful. During the networking hour that followed, attendees lingered to ask questions, seek mentorship, and connect with speakers. It was clear that the event created not only opportunities, but possibilities.

AABANY extends its deepest gratitude to the Kings County District Attorney’s Office, NAPIPA, DA Eric Gonzalez, the moderators, panelists, and all attendees. Pathways to Careers in Government & Justice illuminated the rich landscape of public-sector careers and reminded aspiring attorneys why representation, integrity, and service matter.

We look forward to continuing programs that uplift emerging leaders and strengthen the pipeline of dedicated AAPI public servants across New York.

To learn more about the Prosecutors Committee at AABANY, click here.

To learn more about the Student Outreach Committee at AABANY, click here.